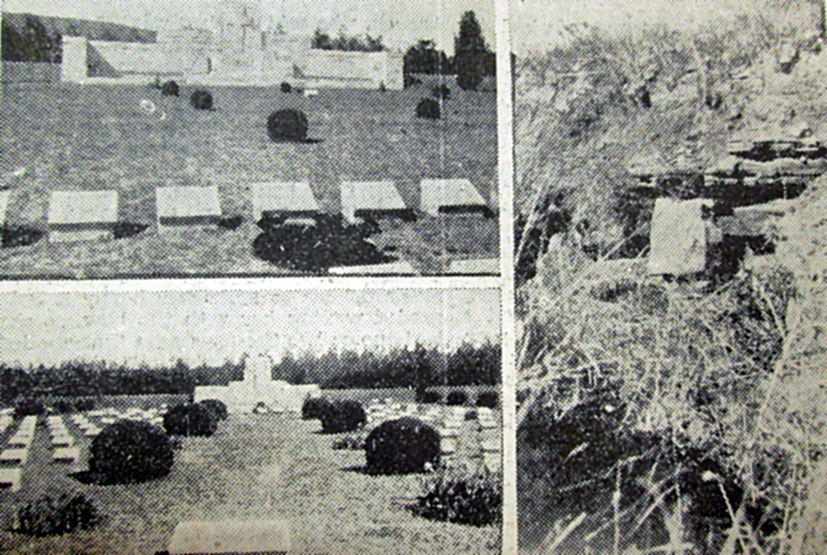

Nearly 20 years after Gallipoli, a Lutonian paid a visit and took these pictures of the Anzac and Hill 10 Rosemary cemeteries and Turkish trenches still visible on Achi Baba.

On December 7th, 1915, the British Government finally sanctioned the evacuation of Gallipoli by British and Empire troops. It was a campaign that had ultimately proved foolhardy after a badly handled start. The heroism of troops like the 1/5th Bedfords (the Yellow Devils) was the only bright spot, if at a high cost in terms of lives and men wounded and afflicted by dysentery.

On December 30th, 1915, the Luton News published a diary of salient dates in the Dardanelles following the official report of the withdrawal of troops.

In a letter also published, Bandmaster W. Goodger, 1/5th Bedfords, pointed out that in the August 15th advance mentioned in the Luton News list, the 10th Irish Division and the 162nd Brigade took the heaviest work. The Brigade at that time consisted of the 1/5th Bedfords and the 10th and 11th London Regiment.

Bandmaster Goodger, who was in hospital at Nottingham, wrote: "For the fine work accomplished by our regiment and also in memory of the dear comrades we lost, and the noble manner in which we were led by Col Brighten on that day, I trust you will give it publicity."

The last British troops involved in the Gallipoli withdrawal were evacuated on January 9th, 1916. A few days later, on January 14th, the Beds Advertiser gave its assessment of the Dardanelles campaign.

It wrote: "Happily this ill-starred episode is ended. Foreign newspapers tell us that there is joy in Constantinople, but, however that may be, there is heartfelt relief and satisfaction in England at the abandonment of the expedition, and felicitations have been general on the brilliant manner in which the evacuation has been accomplished. By providential favour, both the withdrawal from Suvla Bay and Gallipoli have been carried out at a minimum sacrifice of life and infliction of casualties, whereat we all rejoice.

It wrote: "Happily this ill-starred episode is ended. Foreign newspapers tell us that there is joy in Constantinople, but, however that may be, there is heartfelt relief and satisfaction in England at the abandonment of the expedition, and felicitations have been general on the brilliant manner in which the evacuation has been accomplished. By providential favour, both the withdrawal from Suvla Bay and Gallipoli have been carried out at a minimum sacrifice of life and infliction of casualties, whereat we all rejoice.

"Thus closes one of the most disastrous chapters in the history of the present war. Ill-conceived, marked by indecision and a deadly inertia fatal to its success, it has proved terribly costly in its toll of human life to say nothing of treasure and material. The only redeeming feature is the unexampled and unforgettable bravery of the young and inexperienced but dauntless units which took a hand in it.

"One can hardly think of the tremendous sacrifice - so nobly grand, yet unavailing - of our own brave lads and their Australian cousins, without the suspicion of a lump in the throat. Though unavailing, their brave and valiant struggle constitutes an epic of grandeur and self-sacrifice hard to match in Britain's annals. Tremendous indeed has been the toll exacted as the price of the magnificent but disastrous adventure.

"An impossible task, we have all along opined. Yet if leaders could but have risen to the height of their possibilities, how different might have been the sequel."

One man who was not rejoicing was the First Lord of the Admiralty, a young Winston Churchill (pictured right), who was largely blamed for the poor planning of the campaign and its ultimate failure. He was forced to resign, while venting his wrath on Sir Charles Monro, who succeeded Sir Ian Hamilton in command at Gallipoli, and had ordered the evacuation following the Government sanction. The withdrawal was the only part of the adventure successfully accomplished. However, Churchill said Monro "came, saw and capitulated" and then unsuccessfully sought to vindicate his own part in the campaign at an inquiry.