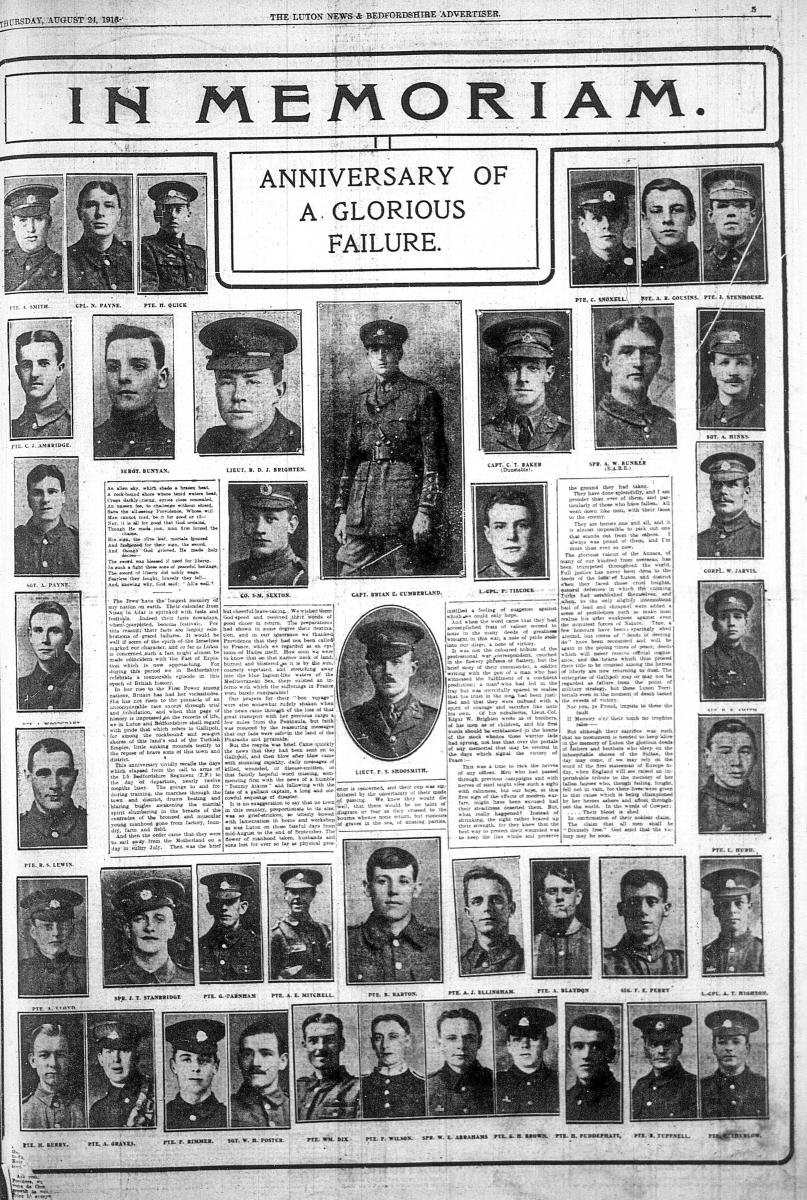

- Luton News commemoration of local men who fell at Gallipoli, published in 1916.

Under the heading “The Tragedy of Gallipoli,” the Beds & Herts Saturday Telegraph of November 1st, 1919, published a personal account of the ill-starred campaign, given in a lecture at Park Street Baptist Church the previous Wednesday by Brigadier-General J. Penry Davey CMG, Principal Chaplain to the United Board.

Said the Saturday Telegraph in its introduction to the report: “There have, indeed been few, if any, stories in the history of all wars which have been marked by such noble fighting in the face of difficulties so tremendous as those which characterised the fighting on the Peninsular, and in the thought that all this sacrifice was in vain, that nothing was gained by the operation there, and that the rivers of blood which flowed among the rocks and crags of that grim country flowed in a cause that was doomed to failure, there is sadness indeed.

“The town of Luton has a peculiarly poignant interest in this campaign, for it was there that so many local men lost their lives. And we say we shall be understood, therefore, when we say it was with emotions stronger than ordinary interest that the gathering heard from the lips of the Brigadier-General as account of the fighting – from the landing to the evacuation – in Gallipoli.”

His story, said the Saturday Telegraph, was instructive and enlightening, and the descriptions of the soldiers from Turkish fire, flies, lack of water, disease and other causes was most touching.

But in the course of his lecture, the Brigadier-General observed: “It is not for me to criticise the campaign, for I am still a soldier. I shall not say whether I think it was wise or unwise. It is not mine to criticise, but this I may say: The campaign developed into what is known as a sheer frontal attack. At first this seemed a possible proposition, but we have learned during 4½ years of terrible war that a frontal attack under modern conditions is impossible.

Another striking statement was the following: “Let me pay this compliment to the Turkish soldier.

If he had played the same game on the Peninsular as the Germans did in France we could never have lived there. He could have blown us off.

“A hospital could never have existed had he done as the Germans did. Our only Casualty Clearing Station and hospital was well in his sight and range, and the Turks were daily firing over it. Occasionally a shell would fall short and drop into the hospital, and men already wounded – wounded to death many of them – would again fall victims to the Turkish fire. But I do not think the Turks would ever put a shell into the hospital wilfully.

“I remember, however, one occasion when they shelled the dressing station for two hours. I was in it, and we could not understand it, for such a thing had never happened before. Suddenly it dawned upon somebody that our Sgt-Major had put up the Union Jack above the Red Cross flag. Directly we took it down the shelling ceased, and we had no more fire on that spot from their guns. In France I have known of deliberate shelling of C.C.S. and hospitals.

“Many, many things were, of course, chivalrous, gallant and great on the side of the enemy, but our men fighting continually a terrible struggle against numbers infinitely superior to their own, held on in spite of all difficulties.”

Dealing with the landing at Gallipoli, the lecturer described the formation of the Peninsular, which, he said, was shaped like a boot, and completely surrounded by cliffs. These made it frightfully difficult to attempt to land troops, and the only opportunities of getting them ashore were afforded by narrow gullies between the cliffs, and even these the Turks had fortified.

Dealing with the landing at Gallipoli, the lecturer described the formation of the Peninsular, which, he said, was shaped like a boot, and completely surrounded by cliffs. These made it frightfully difficult to attempt to land troops, and the only opportunities of getting them ashore were afforded by narrow gullies between the cliffs, and even these the Turks had fortified.

The Turks held the place with every advantage, for the country was a natural fortification and gave every possible natural assistance to the holders against any attacking party. The upper portions were in a kind of spoon, scooped out of the rock. They could not fire at this position, and their only chance was to pitch a shall into the “spoon”.

The landing which was made at dawn on April 25th, 1915, was supposed to be from five places dignified by the name of beaches, lettered S, V. W. X and Y. Among the attacking troops was part of the Royal Naval Division, composed of schoolboys, straight from English colleges, who displayed the greatest valour in the subsequent operations.

At the hour of the attack troops were brought up in all kinds of vessels, from paddle steamers to battleships, and from men-o'-war to destroyers. These men were transferred to small boats, preparatory to being towed to the shore. There was dead silence from the Turkish forts, and it was thought by many of them that the landing would be unopposed. On 'S' beach the landing was successfully carried out, in spite of the swift current, by 7.30, with only about 50 casualties.

Describing the difficulties of the landing and ascent, the lecturer asked his hearers to imagine a slight gully running up the side of the church building, with defences above of machine guns, field artillery and rifles pouring down shells and bullets upon the climbers. They had to leave the tugs and lighters which brought them to the shallow water, struggle ashore and dash across a narrow strip of sand for the foot of the cliffs.

No sooner had the first men left the boats than the silence was broken by the sound of a hellish fire which burst from the tops of the cliffs. Struggling in the face of what seemed hell itself, the gallant lads faced that withering fire, and toiled little by little upward on those terrible cliffs, and gained the top. No eulogium could do them justice, for they were fighting numbers at least twenty to one greater than their own.

On 'X' Beach the Munster Fusiliers had great trouble with the huge masses of barbed wire with which their gully – the only pathway to the top – was barred. The wire cutters supplied in those early days were of very little use, and with these most inadequate tools the men had to standing, without covering and exposed to the fire of the enemy, cutting, cutting, cutting away at the masses of wire.

The lecturer also spoke of the part played in the landing of the 'River Clyde,' and old collier steamer used for bringing up troops. By some means unknown the collier beached before her time, and her 1,000 men were thrown out upon the sand before the men from the other vessels who were to support them. Immediately a mass of blazing flame flashed out from the tops of the cliffs, right down upon the thousand men below.

Men fell by the hundreds, amidst the shrieks of the wounded and the groans of the dying. Of the thousand, very, very few lived to cross the 30 yards of sand and reach the foot of the rocks. The some of the rafts and tugs bringing men from the larger vessels drifted back from the shallows into deep water before the men could disembark, and floated about, an open mark for the enemy's fire.

A strong current – always to be found in the Dardanelles narrows – hindered the work of disembarkation, and during the operations Brigadier-General Napier, with his Brigade Major and Adjutant, were killed.

Speaking of the awful casualties, Brigadier Davey said: “I would not dare to tell you how many men were lost on this occasion before we reached the shelter of the cliffs, and had it not been for the old 'River Clyde,' which afforded a modicum of shelter for those in the boats, very few would have got through at all.”

The result of these operations was that the British got a small footing upon the Peninsular, but how small it was they could not realise. They were never out of range of the Turkish guns, and they were always cramped for 'elbow-room'.

In the summer the life was terrible, but the spirit of the men was wonderful. He (the speaker) had to go seven weeks without a shave, and a month without even an attempt at a wash. He did not know that he had any feeling at all, except that he felt like a bit of baked crust.

Water – especially fresh water – was very precious, and, as they had barely enough to drink, it would be seen that water was never used for washing. If they wanted to wash they had to go down to the sea and perform their ablutions in salt water and 'well what sort of a wash can a man get in salt water?' The scarcity of water was due to the fact that it had all to be brought to the country by sea in casks.

Then there were the troubles of dysentery, which was largely caused by the flies, and of shortage of provisions. If one lifted a slice of 'plum and apple' to their mouth in the ordinary way they got a mouthful of 'plum and apple' and flies, so one had to cover the jam with the hand and knock off the flies until the slice was between the teeth.

The lecturer also mentioned that on ordinary days when no attack was being made more men were lost in the rest camps behind the lines from dysentery and stray shells than in the front line trenches.

Further, they never had sufficient forces to cope with the numbers of the enemy, and so things went on in this terrible way until January 9th, 1916, when Gallipoli was finally evacuated.

- Luton veterans commemorating Gallipoli Day in 1953.