Although the Peace Day riots had no parallel in local history, rioting had not exactly been conspicuous by its absence in the town, said the Luton Reporter in a special report in July 1919.

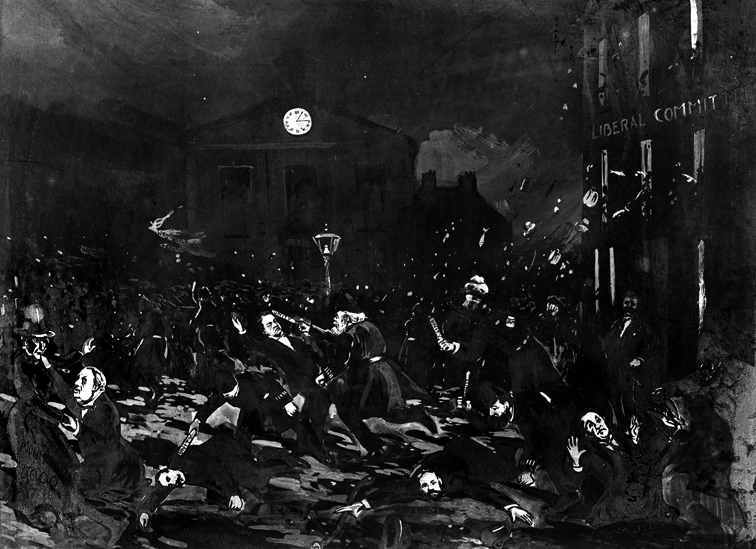

The two riots which used to be most spoken of before July 19th were the 1883 disturbances associated with the first coming to Luton of the Salvation Army and the 1895 election riots [illustrated, right, as a satirical image with faces of prominent political figures of the time included], but local chronicles give records of riots as far back as the 18th century.

The two riots which used to be most spoken of before July 19th were the 1883 disturbances associated with the first coming to Luton of the Salvation Army and the 1895 election riots [illustrated, right, as a satirical image with faces of prominent political figures of the time included], but local chronicles give records of riots as far back as the 18th century.

The earliest that can be traced after the days of the Civil War occurred in the summer of 1795, a year noted for a great flood which covered meadows near the river to a depth of six feet, causing water to pour into homes and completely cut off the town from vehicular traffic. Corn at that time was both scarce and dear, and the action of someone coming from St Albans way in purchasing the little that came into the local market so provoked the people of Luton that they determined to prevent it.

On market day a mob, consisting chiefly of women of the town and neighbouring villages, who had come in to sell their plait, rose and seized a wagon, threw out the sacks of wheat and would not suffer any to be taken away. Towards evening the menfolk also began to riot, and it was found necessary to call out the soldiery. They put an end to the affair without further mischief, but for some time afterwards the removal of wheat had to be surreptitiously effected in the night.

Only five years afterwards the old statute fair produced a riot between civilians and soldiers, and then in 1854, the year in which the first interments were made in the general and church cemeteries, there were bread and bonnet riots. As these incidents occurred before Luton had a local newspaper published, details are not set out.

An even more exciting affair was a series of disturbances which arose between a section of the inhabitants and members of the Salvation Army in August 1883, the year after the opening of the Bute Hospital. The action of the old Army in parading the streets with band music was considered a desecration of the Sabbath and, when one night the Salvationists from No. 1 barracks assembled near the Ames Memorial drinking fountain on the asphalt in front of the Corn Exchange while the Town Brass Band was playing opposite the fountain, a crowd of several hundreds took sides against the Army and set up a hostile demonstration.

Words were followed by blows which culminated in police court proceedings. A chronicler who described the scene of disorder and uproar ascribed the blame to the "somewhat reckless audacity of the Salvation Army officer".

More disorderly scenes followed on succeeding nights, stone and cabbage sticks being thrown at members of the Army and the ranks of their procession broken, and at the request of the then head constable the Salvation Army desisted from further processions until the Sunday night.

Their revival furnished a state of unprecedented excitement. Members of the Army were maltreated by a mob, and the Captain was so badly handled that he was rescued by some of his soldiers "more dead than alive" and sought refuge in the Plait Hall until an opportunity presented itself for him to escape by a side door.

These happenings resulted in the then Mayor, John Dawson, issuing a proclamation calling upon the Salvation Army to discontinue their processions as being likely to cause a breach of the peace. But General Booth [founder of the Salvation Army] took exception to this and insisted on the rights of the Army to carry on. The General was in a position to cite legal decisions in support of his contention that the processions were perfectly lawful and entitled to protection from the guardians of the peace. A compromise was arranged whereby the Salvation Army agreed to consider a proposal for a modified form of processioning upon the local authority withdrawing their proclamation and affording proper protection for the legal exercise of their rights.

Steps were taken to meet the emergency by the swearing in of 90 inhabitants as special constables, having a white band round the arm as a distinguishing badge. This number was subsequently increased to 150, and the sequel was that on one day the magistrates were engaged for five hours dealing with charges resulting from the rioting.

On July 26th, 1895, came the notorious election riot after Mr T. Gair Ashton (later Lord Ashton of Hyde) had been declared MP for South Beds, in succession to Mr S. Howard Whitbread, by a majority of 186 over Col Duke.

King Street was the storm centre, and stone throwing was very rife. On two occasions Deputy Mayor Asher Hucklesby read the Riot Act, and the street was cleared by the police with drawn truncheons. To hold the fort Chief Constable David Teale secured the assistance of the fire brigade and a number of civilians, but they were unable to cope with the crowd, which increased and grew more violent and threatening.

In the end the services of 46 members of the Metropolitan Police were requisitioned. Within ten minutes of their arrival they effected a complete transformation by their unceremonious methods of enforcing order, and the next night reinforcements of mounted men were sent from London to quell a renewal of the rioting.

Within two days the London police were able to return and leave the town quite quietly, but it cost the borough about £300 for police assistance and damage to property. A dozen men were brought before the magistrates on rioting charges, but all got off.

[The Luton Reporter, July 29th, 1919]

[The late James Dyer and John Dony in their book, The Story of Luton (1975 revision), said the 1895 rioting arose because there was a feeling that prominent local solicitor Mr H. W. Lathom, who was to feature in many World War One court cases, had materially affected the result by changing sides during the election. The riot began with the breaking of all of the windows in his King Street offices, followed by an orgy of window breaking all over the town centre. Many Lutonians spent the night in the fields, not daring to return.]